Hurricanes are not just a coastal problem. Life and property can also be at risk hundreds of miles inland. The hazards, however, are not the same for all locations.

Most residents in hurricane prone areas understand how intense the winds can be. However, many may not realize -- or prepare for -- other hazards a storm presents, several of which that are far more deadly than the wind.

Understanding your risk is the first step to preparing for the possible life-altering effects from a storm.

When you live on the coast, you are at risk from ALL hazards of a hurricane.

When you live close to the coast, you are most at risk from extreme wind, power outages and flooding. However, depending on your elevation and proximity to water, you could also be at risk from a storm surge.

Inland residents are at risk of tornadoes, wind damage, power outages, and flooding from hurricanes.

Storm surge is often misunderstood, extremely complex to forecast, and even more difficult to visualize.

Nearly half of all hurricane-related fatalities have come from the surge, according to a National Hurricane Center study that looked at direct deaths from tropical cyclones between 1963 and 2012.

Storm surge can be best described as water that is pushed over the shoreline by the force of the winds. It takes the shape of a broad, rolling hill of water. It can move inland at the rate of up to one mile every three or four minutes. The surge height can be up to two stories tall along the coast and can flood communities and neighborhoods several miles inland. The water is often driven by hurricane force winds, moving at a rate of up to one mile every four minutes. It can also be filled with dangerous debris, sewage, and electrical currents from fallen power lines.

The height of storm surge in a particular area also depends on the slope of the continental shelf. A shallow slope near the coast will allow a greater surge to inundate coastal communities, such as Gulf Coast states. Communities along a steeper continental shelf will generally not see as much surge inundation.

In 2010, 39% of the nation’s population lived in counties that were directly on a shoreline. That population is projected to increase by an additional 8% in 2020. Much of the United State’s densely populated coastlines lie less than 10 feet above mean sea level. The city of New Orleans, for example, is built below sea level, a factor which contributed to significant loss of life when Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005.

Storm surge is often misunderstood, extremely complex to forecast, and even more difficult to visualize.

Nearly half of all hurricane-related fatalities have come from the surge, according to a National Hurricane Center study that looked at direct deaths from tropical cyclones between 1963 and 2012.

Storm surge can be best described as water that is pushed over the shoreline by the force of the winds. It takes the shape of a broad, rolling hill of water. It can move inland at the rate of up to one mile every three or four minutes. The surge height can be up to two stories tall along the coast and can flood communities and neighborhoods several miles inland. The water is often driven by hurricane force winds, moving at a rate of up to one mile every four minutes. It can also be filled with dangerous debris, sewage, and electrical currents from fallen power lines.

The height of storm surge in a particular area also depends on the slope of the continental shelf. A shallow slope near the coast will allow a greater surge to inundate coastal communities, such as Gulf Coast states. Communities along a steeper continental shelf will generally not see as much surge inundation.

In 2010, 39% of the nation’s population lived in counties that were directly on a shoreline. That population is projected to increase by an additional 8% in 2020. Much of the United State’s densely populated coastlines lie less than 10 feet above mean sea level. The city of New Orleans, for example, is built below sea level, a factor which contributed to significant loss of life when Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005.

Tropical cyclones are known for their powerful winds, and they are not just confined to coastal areas. Hurricane-force winds can travel dozens of miles inland after a hurricane makes landfall, causing considerable structural damage and power outages that can last days, maybe even weeks.

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale categorizes a storm from 1 to 5 based on the intensity of the winds. However, when the National Hurricane Center issues a statement to the public concerning the wind and category, that value is for sustained winds only. The hurricane scale does not include gusts or squalls.

The highest wind speeds are typically found in the eye wall of the hurricane and generally in the area to right of the eye, known as the right-front quadrant. This section of the storm tends to also have the most damaging storm surge. Areas that are forecast to go through this quadrant typically experience the heaviest damage. This powerful quadrant can sustain its strength over land for some time before the tropical cyclone begins to weaken.

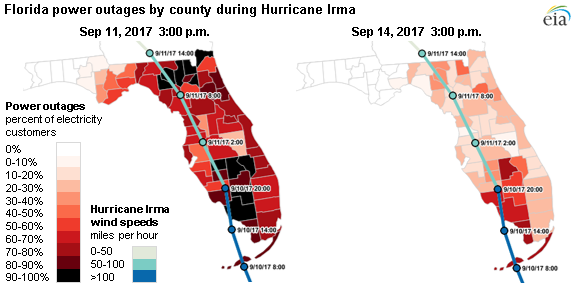

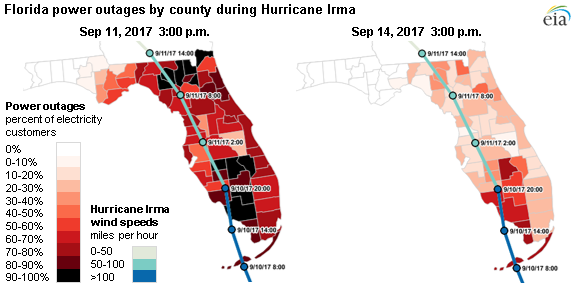

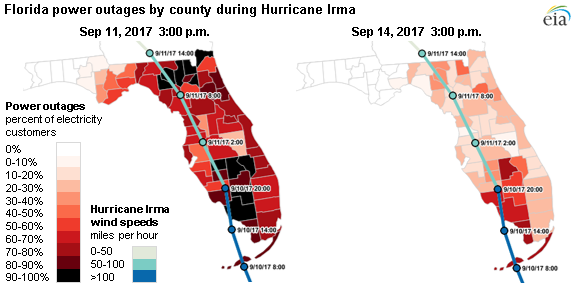

Power outages from Hurricane Irma in 2017 were reported in every Florida county except five. In fact, some of the most widespread outages occurred more than 200 miles from where it made landfall in portions of northeast Florida. Wind speeds in these areas only reached tropical storm force (39 to 73 mph), but that was still strong enough to knock down trees and bring down power lines.

In 2018, Category 5 Hurricane Michael came ashore near Mexico Beach, Florida. Areas along the shoreline experienced catastrophic damage from winds up to 160 mph. The storm maintained its major hurricane strength as it pushed into Georgia, more than 60 miles from where it came ashore, continuing to flatten homes and topple trees. The strong winds from Michael also caused extensive power outages as far north as Virginia, more than 24 hours after landfall.

Tropical cyclones are known for their powerful winds, and they are not just confined to coastal areas. Hurricane-force winds can travel dozens of miles inland after a hurricane makes landfall, causing considerable structural damage and power outages that can last days, maybe even weeks.

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale categorizes a storm from 1 to 5 based on the intensity of the winds. However, when the National Hurricane Center issues a statement to the public concerning the wind and category, that value is for sustained winds only. The hurricane scale does not include gusts or squalls.

The highest wind speeds are typically found in the eye wall of the hurricane and generally in the area to right of the eye, known as the right-front quadrant. This section of the storm tends to also have the most damaging storm surge. Areas that are forecast to go through this quadrant typically experience the heaviest damage. This powerful quadrant can sustain its strength over land for some time before the tropical cyclone begins to weaken.

Power outages from Hurricane Irma in 2017 were reported in every Florida county except five. In fact, some of the most widespread outages occurred more than 200 miles from where it made landfall in portions of northeast Florida. Wind speeds in these areas only reached tropical storm force (39 to 73 mph), but that was still strong enough to knock down trees and bring down power lines.

In 2018, Category 5 Hurricane Michael came ashore near Mexico Beach, Florida. Areas along the shoreline experienced catastrophic damage from winds up to 160 mph. The storm maintained its major hurricane strength as it pushed into Georgia, more than 60 miles from where it came ashore, continuing to flatten homes and topple trees. The strong winds from Michael also caused extensive power outages as far north as Virginia, more than 24 hours after landfall.

Tropical cyclones are known for their powerful winds, and they are not just confined to coastal areas. Hurricane-force winds can travel dozens of miles inland after a hurricane makes landfall, causing considerable structural damage and power outages that can last days, maybe even weeks.

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale categorizes a storm from 1 to 5 based on the intensity of the winds. However, when the National Hurricane Center issues a statement to the public concerning the wind and category, that value is for sustained winds only. The hurricane scale does not include gusts or squalls.

The highest wind speeds are typically found in the eye wall of the hurricane and generally in the area to right of the eye, known as the right-front quadrant. This section of the storm tends to also have the most damaging storm surge. Areas that are forecast to go through this quadrant typically experience the heaviest damage. This powerful quadrant can sustain its strength over land for some time before the tropical cyclone begins to weaken.

Power outages from Hurricane Irma in 2017 were reported in every Florida county except five. In fact, some of the most widespread outages occurred more than 200 miles from where it made landfall in portions of northeast Florida. Wind speeds in these areas only reached tropical storm force (39 to 73 mph), but that was still strong enough to knock down trees and bring down power lines.

In 2018, Category 5 Hurricane Michael came ashore near Mexico Beach, Florida. Areas along the shoreline experienced catastrophic damage from winds up to 160 mph. The storm maintained its major hurricane strength as it pushed into Georgia, more than 60 miles from where it came ashore, continuing to flatten homes and topple trees. The strong winds from Michael also caused extensive power outages as far north as Virginia, more than 24 hours after landfall.

Tropical storms and hurricanes also threaten the United States with torrential rains and flooding. Even after the strong winds have diminished, the flooding potential of these storms can remain for several days.

Since 1970, nearly 60% of the 600 deaths due to floods associated with tropical cyclones occurred inland from the storm’s landfall. Of that 60%, almost a fourth (23%) of U.S. tropical cyclone deaths occur to people who drown in, or attempting to abandon, their cars.

It is a common misconception to think that the stronger the storm is, the greater the potential for flooding. This is not always the case. In fact, large and slow moving tropical cyclones, regardless of strength, are the ones that usually produce the most flooding. This was evident with Tropical Storm Allison in 2001 which devastated portions of Southeast Texas with severe flooding, despite only having maximum winds of 60 mph.

Sixteen years later it would happen again, in the same area. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey came ashore as a major Category 4 hurricane before quickly weakening over southeast Texas. Although Harvey quickly weakened to a Tropical Storm, the system became almost stationary over the region for days. Southeast Texas saw the worst of the flooding as heavy rains delivered more than 40 inches of rain to some areas in less than 48 hours.

Tropical storms and hurricanes also threaten the United States with torrential rains and flooding. Even after the strong winds have diminished, the flooding potential of these storms can remain for several days.

Since 1970, nearly 60% of the 600 deaths due to floods associated with tropical cyclones occurred inland from the storm’s landfall. Of that 60%, almost a fourth (23%) of U.S. tropical cyclone deaths occur to people who drown in, or attempting to abandon, their cars.

It is a common misconception to think that the stronger the storm is, the greater the potential for flooding. This is not always the case. In fact, large and slow moving tropical cyclones, regardless of strength, are the ones that usually produce the most flooding. This was evident with Tropical Storm Allison in 2001 which devastated portions of Southeast Texas with severe flooding, despite only having maximum winds of 60 mph.

Sixteen years later it would happen again, in the same area. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey came ashore as a major Category 4 hurricane before quickly weakening over southeast Texas. Although Harvey quickly weakened to a Tropical Storm, the system became almost stationary over the region for days. Southeast Texas saw the worst of the flooding as heavy rains delivered more than 40 inches of rain to some areas in less than 48 hours.

Tropical cyclones often produce tornadoes, which can contribute to the overall destructive power of a storm. Similar to storm surge and extreme wind, tornadoes are more likely to occur in the right-front quadrant of the hurricane relative to its motion. However, they can also be found throughout the storm.

Tornadoes associated with tropical cyclones are usually less intense than those that occur in Tornado Alley and Dixie Alley. They can occur for days after landfall, even when a hurricane dissipates to a remnant low. Although these tornadoes are generally weak, the effects of tornadoes can produce substantial damage for anyone in the path of an approaching hurricane.

Tropical cyclones often produce tornadoes, which can contribute to the overall destructive power of a storm. Similar to storm surge and extreme wind, tornadoes are more likely to occur in the right-front quadrant of the hurricane relative to its motion. However, they can also be found throughout the storm.

Tornadoes associated with tropical cyclones are usually less intense than those that occur in Tornado Alley and Dixie Alley. They can occur for days after landfall, even when a hurricane dissipates to a remnant low. Although these tornadoes are generally weak, the effects of tornadoes can produce substantial damage for anyone in the path of an approaching hurricane.

Tropical cyclones often produce tornadoes, which can contribute to the overall destructive power of a storm. Similar to storm surge and extreme wind, tornadoes are more likely to occur in the right-front quadrant of the hurricane relative to its motion. However, they can also be found throughout the storm.

Tornadoes associated with tropical cyclones are usually less intense than those that occur in Tornado Alley and Dixie Alley. They can occur for days after landfall, even when a hurricane dissipates to a remnant low. Although these tornadoes are generally weak, the effects of tornadoes can produce substantial damage for anyone in the path of an approaching hurricane.

The official start to the North Atlantic Hurricane Season begins June 1 and lasts through Nov. 30.

Developing and reviewing an evacuation plan is crucial as hurricane season draws near. Learn your evacuation zone, and know where to go in the event of an evacuation order.

Collect and assemble a disaster supply which includes food, water, medication, important documents, and sentimental items.

Strengthen your home and check on family, friends and neighbors. Help individuals collect supplies before the storm and assist them with evacuation if ordered to do so. Check in on them, especially the elderly, after the storm has passed and it is safe to do so.

Hurricane season is approaching, and with the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery ongoing, it is now more important than ever to be prepared for the next storm.